Aida

Details

In Brief

The vulnerable protagonists of Aida face an agonising moral dilemma: to what should they be loyal? To their homelands? To their families? Or to their love? The story of the opera is a product of war: not only in its writing, but on the stage as well. The sounds of war resonate throughout the tale of the captive Ethiopian princess and king, and the Egyptian commander brought down by and for love. Although Egypt wins a pyrrhic victory, this triumph desired by so many brings ruin to all who wished for it. This is a story about war, a topic as old as man and which will continue as long as our species. War chooses life or death for millions, divides families and lovers, and permeates warring countries and their people of every order and rank, from pharaoh to slave. But there is one thing that can never be vanquished: the purity of the soul.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: April 4, 2015

Synopsis

Act I

The Ethiopian princess Aida is being held captive in Egypt, although no one knows of her royal origins. Also kept secret is the love between Aida and Ramadès, the young Egyptian military commander.

The high priest announces that the Ethiopians have attacked Egypt again and informs Radamès that Isis has named him to lead the Egyptian forces. Amneris, the pharaoh's daughter, is also in love with Radamès and hopes that if the young general returns victorious, he will marry her. Radamès, however, nourishes the hope that if he wins a victory, he will be able to marry his secret love, Aida, who herself is confronted with the choice of whose victory she should pray for: her lover's or that of her father and her homeland?

Act II

Aida's father attacks Egypt in order to free his daughter, but suffers a defeat. Radamès returns home victorious with Aida's father among the captured soldiers. The pharaoh announces that he will reward Radamès by granting any request of his. The general asks for the Ethiopian prisoners to be set free, but the high priest obstructs this. The pharaoh offers his daughter, and his throne, to Radamès.

Act III

Under cover of night, Aida awaits Radamès, who had invited her to a secret meeting on the bank of the Nile. The princess feels her situation to be hopeless: her beloved is getting ready to marry the pharaoh's daughter, and she cannot return home. Suddenly, her father appears and pressures her mercilessly: he knows that her lover is the enemy's general, and he orders her to lead Radamès into committing treason.

Trusting Aida, Radamès betrays secret military information, at which point Amonasro rushes out and reveals to Radamès that he is the king of Ethiopia.

The jealous Amneris also bursts forth with her entourage, but before she can have the treasonous general arrested, Radamès succeeds in ensuring the escape of both Aida and her father.

Act IV

The despairing Amneris tries to save the life of the man she loves and who has been condemned to death because of her, but Radamès has no wish to live without Aida. The death sentence is carried out, and Radamès is sealed alive in a crypt. In the silent tomb, Aida emerges from her hiding place in order to die together with her love.

Media

Reviews

“The set and décor imagined by Zsolt Khell are colourful and majestic. The artist succeeded in uniting overwhelming historicism and exoticism with the minimalistic design that is fashionable today. The modern context appears in certain places, but only where it was relevant and without overdoing it.”

Jan Falk, Opera News

Opera guide

Introduction

Although it would be truly difficult (and moreover quite improper) to single out especially popular or iconic works from Verdi’s oeuvre, with Aida we are nevertheless compelled to do something of the sort. For what the average person in the street more or less thinks of when it comes to the genre of opera – that is Aida. A multitude of catchy hit melodies, a sequence of exotic spectacles with their awe-inspiring or even smile-inducing pageant scenes, the obligatory love triangle, the several ballet interludes that halt the action, and even the indispensable extreme operatic mode of death (in this case being sealed in a rock tomb) – all are present here. And if we should need further proof, let us only listen to the timeless Triumphal March from Aida resounding in European football stadiums! This triumphant exaltation of typicality, however, carries some risk: we may all too easily forget the opera’s distinctive features and particular merits. For instance, the tableaux – with their horses, triumphal chariots, and so on – inevitably obscure the drama’s intimate, interpersonal dimension, which is at least as important as the Egyptian-Ethiopian conflict. Or the audience, and at times even the directors, may fail to notice the startling degree of passivity in the title role. Aida, while compelled at every moment to show obedience and solidarity in two irreconcilably hostile directions, never truly acts as an agent herself. The Ethiopian princess’s two arias, and indeed her entire vocal part, exert such a magical allure on dramatic sopranos (who by their very nature possess an active stage presence), and on prima donnas in general, that the outpouring of vocal energy often buries the inert character beneath it. And although among Italian operatic heroines the type of passive victim who merely suffers events is by no means rare, it is still noteworthy that Aida’s first and only independent action is to conceal herself in the tomb prepared for Radamès. True, it is thanks to this deed that we have one of the most beautiful love-and-death duets in all opera literature.

Ferenc László

The director’s concept

When the Hungarian State Opera commissioned me with reimagining Aida, the well-known brainchild of Giuseppe Verdi and Antonio Ghislanzoni, apart from the novelty of the task to direct an opera, I was shocked by its dimensions. I am not referring to its physical dimensions, although they might be the first anyone would think of hearing the title Aida: the grandiose sizes, monumental crowds, sets and costumes. It was an enormous challenge to interpret it, to get a grip on the classical Aida tradition and tell it from a point of view no one had attempted before. I was captivated by Freedom Graffiti by Syria-born Tammam Azzam which he had painted on a wall in Beirut about, and in fact, during the Syrian civil war. Although Gustav Klimt is one of my favourite painters, the image struck me for another reason. It showed the agonies and pains of war while telling a tale about the fragility of people and love, and for me, a practicing theatre director, it also confirmed my faith in the amazing power of art.

Thus, it became clear to me that beside the original story of the opera, my Aida will be about war. War that is as old as humankind and will probably end only with man. War that decides the life and death of millions, tears apart loves and families, and has no regard for anyone or anything. War that permeates the countries at war, their citizens of all ranks, from pharaohs to slaves. All the more so because the story of Aida was conceived in war, not only when it was composed, but also on stage. The story of the captive Ethiopian king and princess, the Egyptian captain who falls in love with her and is destroyed for it can all take on new and special depths in light of war that flows through Aida’s story not so much as a hiding stream, but as grandiose as the Nile. In the production, we will see a state devastated by war. They achieve a Pyrrhic victory, and this victory, desired by so many, will bring destruction to all that desired it.

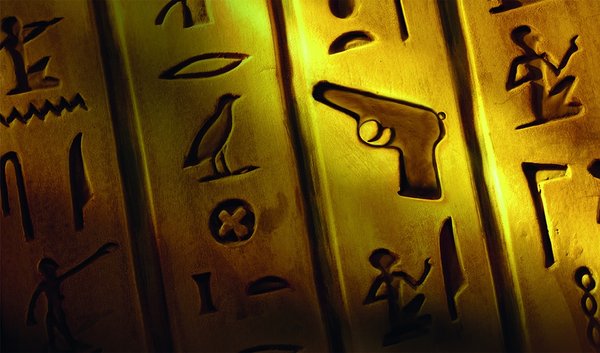

I want my production to become worthy of the death of the lovers at the end of the opera. Choreographer Johanna Bodor expands the world of the warlike and bloodstained sacred temple ceremony of Act I to the entire performance. The Priestesses, who represent the Egyptians’ belief in Osiris in the afterlife, are ever-present albeit invisible to the characters, especially in the vault in Act IV, but they appear every time we feel the wind of the angel of death’ wings. Zsolt Khell designed one site, the continuous deterioration of which suggests the impact of the constant waves of war on Egypt. The walls of the set show the world of Egyptian hieroglyphs and modern military technology simultaneously, the interior lighting of the scenery aims to evoke the sacred nature of ancient Egypt. The weapons and chariots are an anachronistic mix of ancient Egyptian art and modern military technology. Kriszta Remete’s costumes also evoke Egyptian art. Lines known from stone sculptures and wall paintings are interwoven with modern lines, the pleated fabrics are treated with gold, silver, or bronze foils by Kriszta Remete to represent Egyptian hierarchy. The jewellery was designed by a team from Moholy-Nagy University of Arts and design, who used brass to represent Egyptian gold and stainless-steel mesh pressure pipes to create the Ethiopian silver accessories.

János Mohácsi

The costume designer’s thoughts

There is no Aida without fashion. The mystery of the exotic East was given a boost following Napoleon’s African campaign. He discovered Egypt for Europe, and he set a trend of the Empire style in Paris at once. Aida is also characteristic of interpreting oriental themes in post-Napoleonic times. A designer is faced with the question what to make of Aida while working on the visuals of a present-day production. The staging by János Mohácsi, the sets by Zsolt Khell, and my costumes form a triangle of interpretation that allows a new Egyptian Empire to come into being in Budapest. The production places the characters in the coexistence of the modern and the archaic. In this Egyptian culture, behind the rich and shining clothes, signs of digital culture appear on the walls. Among modern machines, the sophisticated use of neutral materials is luxury, complemented by a mania for gold jewellery. As if they were aware of this cultural attitude somehow.

One of my main drives was to create greater unity among the individual groups of characters. For instance, if a character is higher in rank, the blacker their clothes are and the more jewellery they wear. The materials are made of neutral fabrics, on which, however, the pattern is usually printed only. It is a kind of innovation of mine as a designer, the golden light shines from time to time, which combines the real and the unreal in a new clothing style. We can see the golden lustre shining on the dark surfaces, just like the former Empire style, the costumes I have designed also enhances the contrasts between black and gold in the wardrobe of the Egyptian elite. The general uniform of the Egyptian army is based on the khaki colours of the desert, a current trend in military fashion. Printed on these uniforms elements reminiscent of Egyptian clothing appear. The Ethiopians in the opera are distinguished from the Egyptian state black by a deep red. Krisztián Ádám’s jewellery following a minimal style are worthy accessories of the costumes.

Kriszta Remete

On the choreography

We are in Memphis, the story and Verdi’s immensely sensitive music has transported us among the walls of the temple of Ptah. The priests and priestesses pray to Ptah, the god who conceived the world, to bless Egypt and protect the sacred land that can be reached through revenge, killings, and war. Human sacrifice, which was not customary in ancient Egypt, but accepted in other cultures, is used here as a kind of symbol of war. Verdi must have considered this moment important, it was not by chance that he created time in the work and composed music with a sublime atmosphere. This might have been Radamès’ last chance to change his mind.

In our production, a petite, beautiful, gentle, but muscular, vigorous virgin girl dressed in a white dress is sacrificed. A woman who regards it an honour to die on the god’s earthly island in the temple: she is unconditional devotion itself. In fact, she suits Egypt’s political interests. She is sacrificed on the altar of sacred truths and sacred customs. There is a moment in this scene when the virgin and Radamès face each other blindfolded. They are both equal in their vulnerability. The difference between the two of them is that one puts on the blindfold willingly, the other does not. Priests, priestesses, soldiers, and Radamès witness this woman’s sacrifice with reverence. They are deeply touched by her devotion. Her death is exemplary, her self-sacrifice cleans the slate from the looming doubts of tactics and state leadership. The sacred sword is soaked in the virgin’s blood. Radamès and Egypt can go to war now, his morale has been boosted by the sight of the blood sacrifice. Death without a scream, restrained pain, the nobility of faith and self-sacrifice are intertwined with music, which is perhaps the only worthy companion in such a heartbreaking scene.

In the process of creating this scene and during the development of the choreography, there were moments when we felt that if we looked at its message realistically just for a single moment, if we perceived the stage fiction as reality, it would be unbearable. While the everyday world creates events that can make our conscience uneasy, and – although we would like to change so many things – we end up doing nothing, or at least not enough for this story to lose its relevance. When the choreography was completed, the soloists and chorus members also joined in our work, and the final form of the scene took shape. This was the moment when a few of the soloists and chorus members watched the sacrificial dance in shock as they sang. Their expressions changed. That day, it was as if the music we had listened to so many times spoke to us differently.

Johanna Bodor