Die Entführung aus dem Serail

Details

In Brief

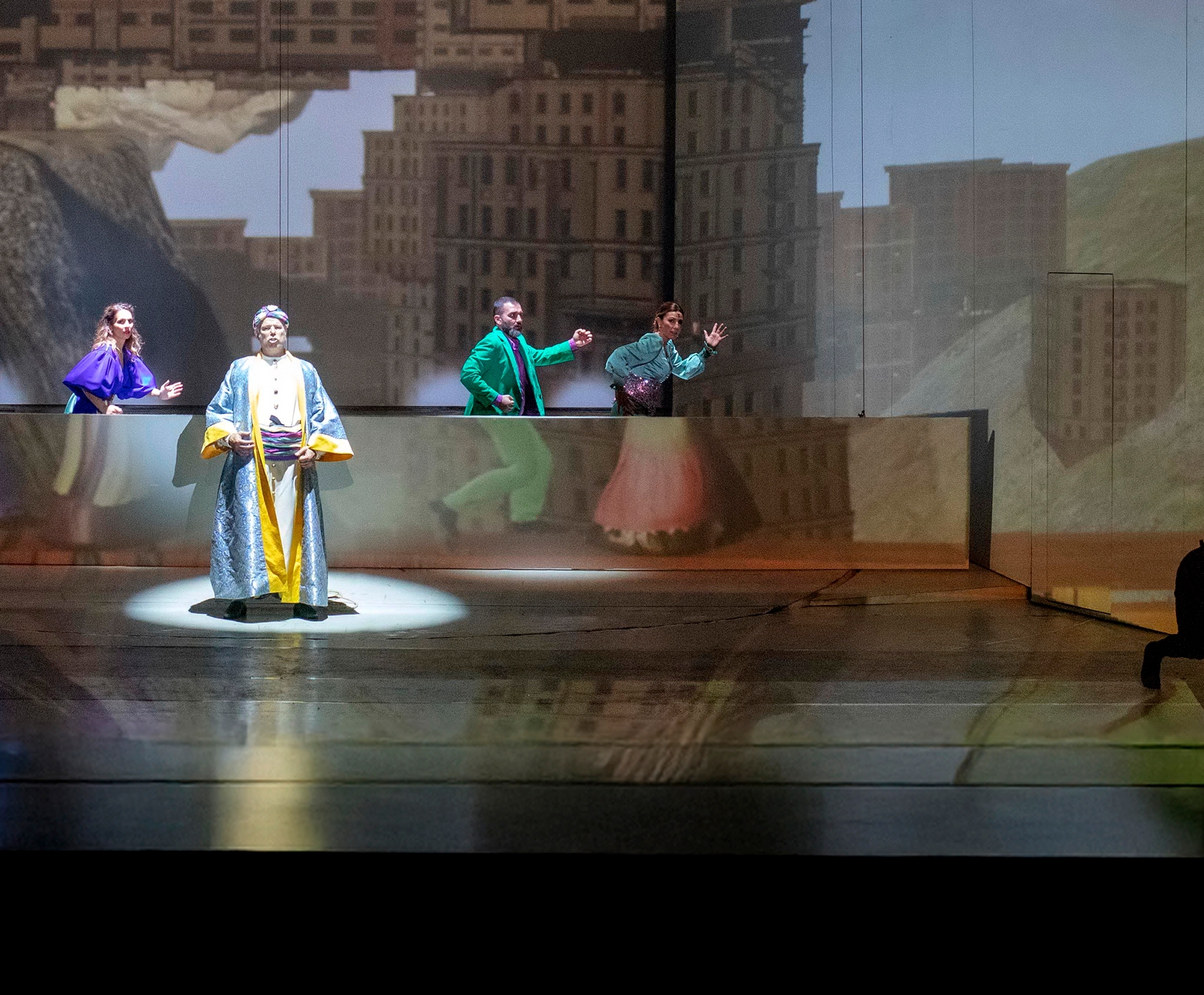

A gripping plot – in this case the story of young lovers fighting to escape the seraglio – is in and of itself one of the keys to a successful dramatic work. However, the varied music written by a twenty-something Mozart, with its freshness and a few oriental touches, makes the singspiel The Abduction from the Seraglio completely irresistible. The production, the first opera staging by Miklós H. Vecsei, a director of Mozartian youthfulness, is sure to be fresh and sometimes a bit irreverent toward operatic traditions also thanks to video projection group Glowing Bulbs and a new Hungarian translation by Dániel Varró.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: April 29, 2022

Synopsis

Part I

Foreigners are rare on Pasha Selim’s lands, this strange, almost magical place. However, this is exactly where Belmonte, a young European nobleman, ends up steering his ship. He has come for his betrothed, Kontstanze, who has fallen into the hands of human traffickers along with her friend, and both are now the captives of Pasha Selim.

Belmonte would immediately hurry to the palace to free everyone, but Osmin, the Pasha’s bad-tempered servant, stops him and drives him away. But Belmonte is not thwarted: he hides and sees that his friends Blonde and Pedrillo are forced to work in the Pasha’s factory. At just the right moment, Belmonte reveals himself to Pedrillo, who tells him that Pasha Selim is bombarding Konstanze with his love. He had taken her on a boat trip for a number of days and the two are just returning.

The Pasha approaches Konstanze gently, attempting to use rational arguments to convince her to love him. However, Konstanze keeps refusing him, telling him she is still in love with her fiancé Belmonte.

With Pedrillo’s help, Belmonte introduces himself to the Pasha as an architect and manages to gain entry to the palace. Although the Pasha has given Blonde to Osmin, allowing her hot-headed and somewhat narrow-minded owner to do as he pleases with her, the young girl is not afraid of him, putting him in his place whenever she feels like it.

Konstanze is increasingly overcome by grief at being separated from her fiancé, which leads the Pasha to issue an ultimatum: he has lost his patience and demands her love from the next day. Konstanze’s reply is yet another strong rejection. Pasha Selim gives up on using kind words and threatens to use force.

Part II

Pedrillo shares the great news with Blonde: Belmonte has arrived to free them! Blonde runs to tell Konstanze while Pedrillo drugs the guard Osmin, incapacitating him. The lovers can now finally meet, and Belmonte tells the others of his plan: he will set fire to Selim’s factory, which is suspicious anyway, and while everyone is occupied with the fire, the four of them will escape with Belmonte’s ship.

Night falls, and the escape starts according to plan. Osmin regains consciousness and sets his dogs on the escapees, forcing them into a corner. When Selim learns of the escape, he is boundlessly hurt and angry. He has the lovers thrown in prison and orders their execution.

At night in their cell, Konstanze and Belmonte pledge their eternal love for one another, and await death happily in each other’s arms. Selim, who was eavesdropping and heard their honest and selfless proclamations of love, finally overcomes his desire for revenge, surrenders Konstanze, and releases the prisoners. Before leaving, the newly released lovers gratefully salute the generous ruler. Only Osmin is unhappy with the events, but no-one listens to him.

Media

Reviews

"Thanks to the Kiégő Izzók team, the screens turned into an exciting, expressive world giving the impression of virtual reality. (…) The people in the seraglio are played by dancers. The choreography of Adrienn Vetési conveys confinement, struggling in bondages, and the wish for freedom to the audience. The strong colours and animal symbolism of Kinga Réta Vecsei’s costumes is a reference to the disenfranchised situation, helplessness and degradation of the women kept in the seraglio besides the splendid environment."

Mariann Tfirst, Art7

Opera guide

Introduction

“The day before yesterday young Stephanie handed me a libretto to be set to music. The libretto is quite good. Its theme is Turkish, its title: Belmonte and Konstanze, or The Abduction from the Seraglio. They want to stage it by mid-September. The Russian Grand Duke is expected here, and Stephanie asked me, if possible, to compose the opera within this short time.” Thus, on 1 August 1781, Mozart informed his father, Leopold, of his promising new operatic project. At that time, Leopold was resentful toward his brilliant and increasingly independent son — both because of his move to Vienna and his marriage plans (Constanze!). The creation of Die Entführung aus dem Serail, however, fits not only within the framework of biography or career-building; it also offers rich cultural, musical, and political motifs without which Mozart’s first completed Viennese stage work would not – or not in the same way – have reached its contemporary audience or posterity.

Let us begin with the Turkish theme, which was considered fashionable and well established in the last third of the eighteenth century, both in Vienna and throughout Europe. The Turks, who less than a century earlier, in 1683, had besieged the imperial city, had by this time, in the spirit of Orientalism, become popular figures in literature and on stage alike. These fictional Turks supplied a ready-made dose of exoticism, sometimes thrilling, sometimes comic; at the same time (like literary Persians or noble savages) they offered a contrast and a mirror to expose the contradictions of Western civilization. By then, moreover, the Turkish style had already appeared in music, providing a favoured colour and technique for composers both great and small. This was the sound world of the janissary music, first encountered, centuries earlier, under wartime circumstances through Turkish military bands. The ensemble of percussion and rhythmic instruments – bass and side drums, cymbals, tambourines, jingles, and the like – proved ideally suited to evoke exotic and martial colour, as well as to paint heightened, ecstatic moods. This was true well before Mozart’s time and for some time afterward too – think, for instance, of the “Turkish March” from Beethoven’s Die Ruinen von Athen.

Then there is the political dimension. It is not so much the semi-official visit of the Russian Grand Duke – the future Tsar Paul I – to Vienna that matters (that visit, incidentally, was conceived in the spirit of an anti-Turkish alliance), since the premiere of Die Entführung did not, in the end, take place in his presence nor at that time. Rather, what is significant is Emperor Joseph II’s Germanizing policy – often condemned from a Hungarian perspective – which in Vienna led to the dismissal of the French court theatre troupe, the temporary sidelining of Italian singers, and, above all, the flourishing of German spoken and musical theatre. In the operatic sphere, this favoured the Singspiel genre – and thus we have arrived at the peculiar performance challenges of Die Entführung aus dem Serail.

In this Mozart work, the opera singers must speak prose between the musical numbers, while Selim Pasha, a key figure for the plot’s outcome, does not sing at all. Both features have long remained problematic: prose rarely feels convincing or appropriate on the operatic stage, and introducing a dramatic actor can easily upset the delicate balance of the piece, especially today, when many productions place Selim’s character entirely at the centre. Yet the vocal parts are ultimately more important than the renegade Pasha’s moral pronouncements, and the singers’ roles raise more intriguing questions than Selim’s magnanimity ever could. How sincere is Constanze’s faithfulness, constancy, and self-sacrificing love, as she performs a string of virtuosic vocal feats? In the third-act duet between Belmonte and Constanze, is there not perhaps too much of the “you die for me” / “I die for you” fervent exchange, accompanied by music so overflowing with emotion and almost melting happiness? And what should we see in Osmin: a comic figure, a truly bloodthirsty villain, or a giant baby raging under the burden of his role? “Who finds so much good too small, / Let him be met with blame and fall.”

Ferenc László