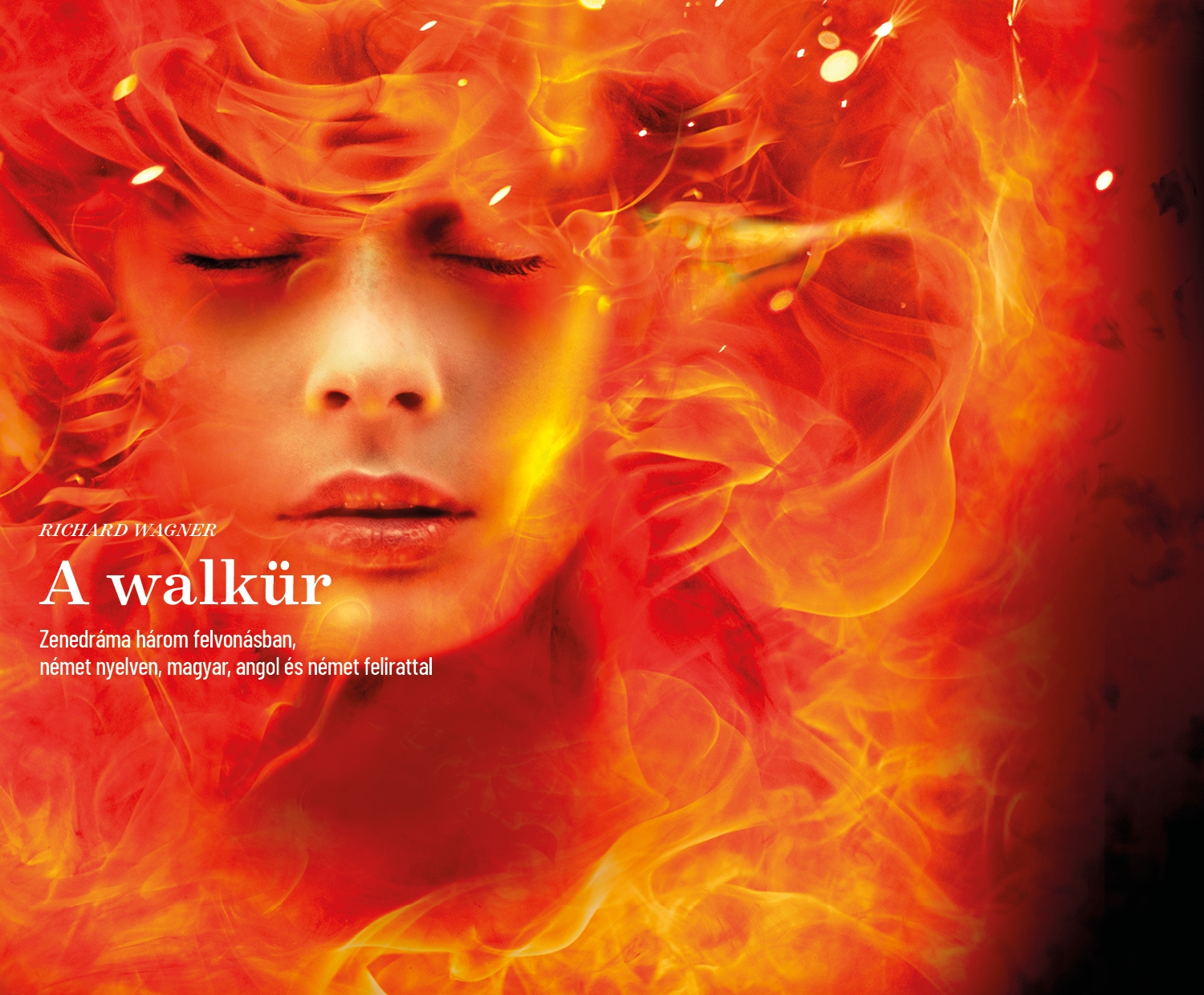

Die Walküre

Details

In Brief

“I've captured a terrific storm of elements and of hearts which gradually calms to Brünnhilde's magic sleep,” Wagner on the score of Die Walküre, in a letter to Ferenc Liszt. Following on the heels of the introductory Das Rheingold, this opera about the tragic love between two of Wotan's children constitutes the start of the more tightly drawn dramatic trilogy. Once again, the laws of the gods clash: can paternal love save a lad who has violated the sanctity of marriage? And what punishments await the woman who protects the as-yet-unborn and innocent hero?

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: March 6, 2016

Synopsis

Media

Reviews

“Musically, it is a genuine sensation, and it is a spectacular experience visually too: stage director and video artist Géza M. Tóth makes Die Walküre glitter, shimmer and blaze on the stage of the Hungarian State Opera.”

Jörn Florian Fuchs, Deutschlandfunk

“M. Tóth Géza’s new Walküre is inventive as well. In the background, the constantly changing, or at least continuously, slowly moving video illustrations by KEDD Animation Studio can be seen. These repeatedly appear on intermediate scrims as well, mystically transforming the action unfolding behind them. Dramaturgically, this often proves effective and well thought out. How enjoyable it is to see Wagner’s Ring myth realized once again in Budapest, something so culpably denied in German director’s theatre. In this Budapest Ring, you can see how consistency and expressive power help to unfold the music even more fully.”

Dr. Klaus Billand, Opernmagazin

„M. Tóth sets his Ring in a not-too-distant future, in which society has bifurcated into a race of divinities who dwell in sleek modern buildings that rise far above the abused proletarians, who endure in a despoiled environment saturated by commercial consumerism. Projections form most of the sets, with glitzy cityscapes and advertisements defining the lower depths, while the gods enjoy health, luxury, and power, represented by complicated mathematical equations covering digital images of the earth and universe. (…) Contrary to many modern productions, there is no room for nonsense or meaningless flights of fancy. Notably, as many directors abstract the ring itself into an intangible commodity such as youth or fossil fuels or liquids, M.Tóth preserves an actual physical ring that drives the action as traditionally as in any production still employing spears and helmets.”

Paul du Quenoy, The European Conservative

Opera guide

Introduction

Die Walküre is in several respects a particularly special part of the tetralogy: partly because it forms a complete whole in itself and is therefore the most frequently performed individual segment, and partly because of its musical-dramaturgical perfection, its electricity, and its perfect synthesis of poetry and music. According to Adorno, Wagner here “reaches a hitherto unknown degree of melodic flexibility, as if the melodic instinct were liberated from the shackles of the small period, as if the force of instinct and expression were to transcend conventional articulations and relations of symmetry.”

Once again, Wagner shatters conventions: opposed to the institution of marriage (which he never held in particularly high esteem), he evokes the mythical image of incestuous sibling love. Moreover, the love of Siegmund and Sieglinde is the only truly ideal and sensual—indeed, physically fulfilled—love in the entire work. After the encounter of Wotan and Erda, which led to the casting away of the accursed ring, the aura of fear is born: the world is in a state of potential, permanent danger (in Fafner’s hands, in Alberich’s desires). Since Wotan is bound by contracts and compromises, he must beget a surrogate hero who can eliminate this fear.

By force of circumstances, Siegmund, who has become an individualist, is the first candidate: taking possession of the sword is the first trial. Accordingly, the first act unfolds within the dramaturgical play of awaiting and recognizing the hero. Hunding simultaneously sees in him both a threat to the communal, clan-based order and a potential seducer of the wife he acquired by force. Fricka recoils in horror at the sight of the “guilty” couple’s love and, exercising her divine authority, renders the success of the heroic undertaking impossible. Wotan’s plan remains a self-deceptive dream. Thanks to Brünnhilde’s rebellion and to the life-affirming alliance between Sieglinde and the Valkyrie, when the unborn Siegfried is saved, the love that challenges the divine order of power is saved as well.

Wagner deploys his distinctive leitmotivic technique in all its splendor and complexity, creating at once dramaturgical-logical connections and links of emotional intensity. Three passages from Die Walküre are indestructible hit numbers: Siegmund’s Spring Song (“Winterstürme wichen dem Wonnemond”), the Ride of the Valkyries, and Wotan’s Fire Magic (“Loge, hör!”). Imre Kertész was initiated into the world of opera by a performance of Die Walküre: “it struck me like some roadside ambush, like an unexpected attack for which I was in no way prepared,” and he adds, “I somehow ended up like the protagonists of another opera by the same composer, Richard Wagner (which at the time I knew only by reputation), Tristan und Isolde, after they had drunk the magic potion: the poison penetrated deep into me, permeated me through and through…”

Zoltán Csehy

Classical, yet modern –In conversation with director Géza M. Tóth

The Hungarian State Opera began producing its new Ring cycle in 2015. To realise the production, Béla Balázs Award recipient and Oscar nominee animation film director, Géza M. Tóth was commissioned, who staged the first three instalments of Wagner’s music drama year after year. Following the reopening of the Opera House in 2022, the production of Götterdämmerung, the concluding piece of the tetralogy put an end to the large-scale enterprise. How do you regard the popularity of Wagner’s magnum opus as a director?

Friendship, love, loyalty, the ability to be satisfied, and to forgive: these are fundamental, eternal human values essential to a healthy society, the importance of which might still fade or disappear – especially at times of crisis. Richard Wagner’s monumental, romantic Ring tetralogy, Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung, is not merely a distant legend of mythological heroes, but a fine reflection of the economic, social and ecological changes and crises of the past two centuries. A parable warning us that it necessarily leads to global catastrophe if people give in to the insatiable desire to possess, and keep exploiting others and their environment at an ever-increasing degree. The tightly woven unit of Wagner’s text, music and stage directions is so exact that following it as closely as possible may in itself be helpful in the creation of a modern production.

Nevertheless, directors often struggle with implementation on stage. What approach did you adopt?

I approach each work analytically, I try to uncover the solution from the given work. In the case of The Ring, two directions seemed obvious: either I take the mythological approach, or social criticism. I felt that by the mythological fabric, Wagner created an opportunity to present his social criticism to the public. In the second half of the 19th century, by making friends with many great philosophers and theoretical historians, Wagner became increasingly sensitive to the social changes in Europe at the time. The basic question of The Ring is how the individual’s social position can be maintained or increased through the power of money. Maybe not everyone wants to move up a notch because they would feel more comfortable there, but because of being afraid of slipping down. The Ring is essentially a presentation of social hierarchical levels. Wagner uses mythological figures to talk about the system created by money and power, in which the desire for more money and more power will be the driving principle that keeps it all alive. At the same time, of course, it raises the question of whether it works in the long term. Is this hierarchical system sustainable? Is there, can there be continuous development?

You try to capture the tetralogy as a whole, instead of dividing it into the individual works.

This is the Wagnerian concept. The composer’s intentions are the most important thing, but it must also be taken into consideration that the production – or, rather, four productions over the course of four years – are created with the singers and musicians we have. I concluded that the logic of the construction of the overall production, that is, its dramaturgy, is fundamental in this approach. In order to achieve both complexity and unity in this direction, I had to accept that an overarching system suitable for all of the settings, no matter how complex and sophisticated, will inevitably become boring and static, and no spatial organisation or set design can be appropriate for every scene while still maintaining the same level of intensity.

This is why I decided to find a logic for arranging the set in a way that is not solely based on form. And it was also clear to me that this opera would not allow the reorganisation of the stage between the scenes, which would break it up into parts too forcefully. As it is a coherent and seamless piece of mythology, the scenes, acts and parts of the tetralogy are all linked to one another with many threads. This should also appear in the logic of the set design and the use of material and space. This was one of the starting points. The other issue is that Wagner included many aspects in the story that are difficult to resolve using conventional stage techniques. (Nymphs swim under the water, fire appears from out of nowhere, two giants enter, someone turns into a dragon before our eyes…) So, I had to find a medium that is suitable for this kind of magic.

Earlier, when I staged St. Matthew Passion, I already experimented with semi-transparent surfaces for projection, which caused the changes in the distribution of light before and behind the materials to result in dream-like effects, and even allowed for the characters to be highlighted or hidden. The overall style combines projected images, lights of various colours and semiotic set elements.

The projected images are, of course, elements of the spectacle, but the lights, the set, the costumes and especially the singers’ performances, movement and presence on stage are equally important. The images will be projected from two points (front and back). It is important to note that this is not a film, but rather a continuously moving visual presence. It would be a mistake to overemphasise this element, as no technique in terms of form should simply be art for art’s sake, and everything should really be about the opera and Wagner. He is the one who heads off on this path from the first note, and continues on it until the closing measure. The projection follows this concept. Of course, we are not going to project images exactly “to the music”, as this would result in a strange illustration that would soon lose its meaning, but the overall visual spectacle will follow the music. So the images do not have to correspond to the specific melodies, but rather to the given musical passage.

What changes have taken place in the visual concept since the premiere of Das Rheingold? How have you and your team built on the lessons sifted from that?

Our production of Rheingold was preceded by several similar productions merging traditional theatre visual design and state-of-art projection technology. This meant that we did not have to make substantial conceptional alterations in Die Walküre relative to Rheingold. We are using slightly richer projected visuals in Die Walküre, but the character of the movement in the projections has remained very similar. The starting point for the visual concept, which hasn’t changed, is for there constantly to be a moving visual presence on the stage. While developing it, we took note that using our technical possibilities as a basis, this would be a horizontal, rectangular image, but it is actually positioned in the space, and not on a film screen or on a monitor. We had to make sure that every shape within the boundaries of the image would be an independent, rational unit.

The other substantive criterion was that in a theatre, due to the lack of light, the primary colour is black, and therefore during the projection black equals nothingness. Only visual elements that are not black show on the projection foils. This way, the process of developing the moving visual materials is completely different from when one is making a film, where black is one of the components within the image. We put more emphasis on using this know-how when developing the visual materials for Die Walküre. At the same time, we also re-used and further developed those visual motifs that we had already created for the previous work. For example, for Wotan’s world plan, we used the same form of universal digital system, suggesting totality, as we did last year. The motif – akin to this – assigned to Siegmund is similarly monumental, without being artificial. Instead, it is composed of constellations of stars, suggesting some kind of order existing since eternity. It evokes the primal, undifferentiated substance that we attempted to depict in the river Rhine.

The fire will appear later in a similar form, another primal element that can have its impact in the visual language of indivisibility and dimensionlessness. For all of this, obviously, the opposite and visual antithesis also appears. Expressed as a horizontal and vertical grid-structure is the endlessly structured, strictly hierarchical world of Hunding, which Fricka, in opposition to Wotan, also represents.

How does the story of Siegfried fit into the thread of your Ring cycle productions which both criticise consumer society in a coherent fashion?

It fits into it perfectly, although “social criticism” is perhaps not the best expression to describe what we are doing. In any case, it was never my aim to interpret the work in a way that would be alien to the author’s original intent. We too relate to the tetralogy as a mythological story, but its visual world is not the primeval Germanic stereotype, prehistoric and shrouded in mist, but rather a similarly fictional and exaggerated world of stories in which the audience can find associations that are generally related to the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. And what emerges within this framework is not a social criticism as such, but an important question that was so characteristic of Wagner and his era: how will the new world order stand the test of time as a universal system in terms of human and traditional social values? And this new order is the consumer society itself, although it was not called that in the 19th century. If we interpret the question in this way, it is no great feat to develop the idea further from there, as Wagner provides a summary of the previous two operas in Siegfried. It’s interesting that one often feels that the tetralogy could actually conclude at the end of Siegfried. The story has been fully rounded out and could really stand on its own two feet as a trilogy without Götterdämmerung.

It does stand on its own nicely. However, without Götterdämmerung, what we would get would be a Hollywood adventure tale with a happy ending. Wouldn’t this interpretation be too optimistic?

It would be a fine, self-contained story this way too, one with a powerful and beautiful message. That in this utterly corrupt world, only love can offer some hope. A love in which the self is dissolved, experiencing total unity with another person instead of one’s own desires, fears (or fearlessness) and identity.

At the end of Götterdämmerung, this same fusion actually takes place…

With the not-negligible difference that this second union entails no hope for the world or the Wotanian world order. But when Brünnhilde and Siegfried meet for the first time, there is a pronouncedly optimistic return to the same primeval dimensionlessness represented by the Rhinemaidens. Here, however, we can see the same thing at an even more elevated level, because the lovers represent not only playfulness and freedom, but also the dual unity I mentioned earlier. Then, along comes a strange and contrasting Tristan-like story in the last part of the tetralogy, where Wagner gives the final answer that the order created by Wotan and then destroyed by Wotan buries everything underneath itself when it collapses.

Due to the restoration of the Opera House, the staging of Götterdämmerung had to be postponed to May 2022. Did the world events that took place during this break influenced you? Did you change anything about the “actualities” of the concept?

We thought in a logical unit, so in 2014 we already knew what how we wanted to present Götterdämmerung, the last instalment of the The Ring. The scenery and set designs, the “graphs” making up the structure of the performance had already been envisaged. The final visual designs, of course, weren’t ready at the time, but the concept of the stage design and the projection were all outlined as well as whether certain elements should be factual or suitable for associations instead. These visual leitmotifs see the tetralogy through, just like the musical leitmotifs. We tried to achieve the pictorial iconography to as diverse as Wagner’s music. All this needed dramaturgical accuracy and consistency. Apart from the aforementioned social criticism aspect, I refrained from including any current social phenomenon directly in The Ring. I had no intention of alluding to the coronavirus epidemic with figures in face masks or gas masks; I didn’t want to depict bored, selfie-chatting gods or drifting refugees looking for a new homeland. It would have been obvious, but I also declined turning the end of Götterdämmerung into some burnt-out or flooded world which we could associate with an ecological disaster. It would have been a trap, a dead end, which I consciously avoided. This kind of “language” is foreign to my theatrical ethos, but more importantly, I believe it is also foreign to Wagner.

Returning to The Ring’s message for today: the tragedy of mankind – or humanity. Do you believe that wanting more instead of enough is the main cause of our “twilight”, our end on earth?

Wagner’s tetralogy presents an experiment: what happens when the material needs and the domination achieved by them over others becomes the measure of value? Or, when it is becomes a model for society. It turns out that almost everything is in this system fails: work is unpaid, the miserable are even more exploited, guest right is no longer sacred, the outlawed are not entitled to legal remedy, friendship hallowed by blood-brotherhood is mocked, love is manipulated, the possible saviours, the “redemptive redeemed” – such as Siegmund, Siegfried, Brünnhilde – are betrayed, and no one is interested in the sage’s advice either... Our archaic, fundamentally essential values are neglected one by one in the model where the main value of “enough” is replaced by “more and more”. For me, it the most interesting, most important message of this great work.

The interviews were conducted by Diána Eszter Mátrai, Eszter Orbán, Tamás Pallós, and Viktória V. Nagy