Maria Stuarda

Details

In Brief

Hungarian premiere

Many of Bergamo-born Gaetano Donizetti's operas have already been staged in Budapest. However, his great operas of historical dramas have so far been neglected, with the exception of Anna Bolena, which has not been performed in decades, either. It was therefore an important moment in 2025 that for the first time ever, Maria Stuarda was presented at the Hungarian State Opera. The bel canto composer, whose works are characteristic of endless and endlessly beautiful melodies, based his opera on Friedrich Schiller's drama of the same title about the last days of the life of the tragic Queen of Scots. The production was staged by Máté Szabó, a director familiar with Donizetti’s world, approaching the work from a psychological perspective.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: May 10, 2025

Synopsis

Act I

At the Palace of Westminster in London, a jousting tournament is held in honour of the French envoy, who has brought a marriage proposal from the King of France to Queen Elizabeth. The union would establish a glorious alliance between the two kingdoms. Elizabeth is uncertain about the decision. She is still in love with the Earl of Leicester, who has recently grown distant from her. Her uncertainty deepens when the celebration is disrupted by protestors demanding mercy for Mary Stuart, the Queen of Scots, who has been imprisoned for many years.

Talbot, Mary’s confidant, also urges for clemency, while Elizabeth’s advisor, Lord Cecil, pushes for signing Mary’s death sentence. He sees the Catholic Mary as a dangerous rival who could claim the throne as a legitimate heir against the Protestant Elizabeth.

The queen summons Leicester. She entrusts him with her ring along with a message for the French envoy, stating that she has taken note of the marriage proposal but has not yet made a decision. Seeing her former lover’s indifference, she leaves angrily.

Talbot privately tells the Earl of Leicester that he visited Mary Stuart in her prison at Fotheringhay. The Queen of Scots sends a letter and a portrait of herself to the earl, asking for his help in pleading her case to Elizabeth. Leicester is ready to risk his life to free Mary. He persuades Elizabeth to visit her cousin in prison under the pretence of a hunting trip. Though jealous and reluctant, the queen agrees.

At Fotheringhay Castle, Mary and her faithful companion in captivity, Anna, enjoy a walk permitted in the park. As Mary wanders among the trees, she recalls memories of her childhood in France. She is willing to renounce the throne if only she could return there. Leicester comes to see her, assures her of his love, and urges her to behave humbly before Elizabeth. A hunting horn sounds – Elizabeth arrives, accompanied by Lord Cecil.

Talbot advises Mary to remain composed. Clinging to her love for Leicester, she indeed acts humbly. She kneels before her royal cousin, pleading for her freedom. Cecil warns Elizabeth not to be fooled by what he sees as a deceitful performance. In a fit of jealousy, the queen begins to insult Mary, accusing her of promiscuity and of having murdered her husband, Henry. The hot-tempered Mary loses control and calls Elizabeth a vulgar whore and the bastard of Anne Boleyn, who desecrates the throne of England. With that, her fate is sealed. The queen summons the guards and has Mary returned to her prison.

Act II

Cecil obtains evidence that Mary was involved in a Catholic conspiracy against Elizabeth. At the Palace of Westminster, the death sentence lies on the queen’s desk. Yet Elizabeth hesitates. If she signs it, she risks inciting the wrath of all Catholic Europe. Cecil urges her to act: every English subject is ready to avenge her death if necessary, but if she does not sign, she endangers her own life. Torn by uncertainty, Elizabeth, upon seeing the approaching Leicester, quickly and indifferently signs the death warrant. She gives it to Cecil with the instruction to carry out the execution the next day. Leicester begs her to withdraw the order, which condemns an innocent woman to death. But Elizabeth is merciless and commands the earl to witness the execution of his beloved.

Lord Cecil brings the news of the execution to Mary in her prison at Fotheringhay Castle. Mary accepts her fate. Her loyal friend Talbot visits her before the bloody hour. She confesses her sins to him: she is haunted by the ghosts of her second husband, Lord Henry Dudley, and her secretary, Rizzio – they died because of her. Talbot grants her absolution, and Mary goes to her death guiltless. She asks Anna and her ladies-in-waiting to pray with her to God rather than weep. She bids a final farewell to the Earl of Leicester as well. In her last words, she turns to God: may her innocently shed blood bring peace, and may He not strike oath-breaking England.

Media

Reviews

„Highly experienced, widely sought-after, and award-winning, Máté Szabó enjoys an excellent reputation, and based on the performance we saw this evening, that reputation is fully deserved. He breathed life into an almost constantly moving plot, which was well complemented by the restrained yet pleasing sets and the lighting concept; there was nothing to complain about regarding the costumes either.”

Pierre Waline, Journal Francophone de Budapest

„Szabó Máté’s new staging was successful in emphasizing what is probably the opera’s greatest strength: two heroines who transcend Romantic female archetypes, and emerge as strong, complex and conflicted human beings.”

Gianmarco Segato, La Scena Musicale

„Csaba Antal’s set design is functional: it employs a basic structure that evokes a marble construction, supplemented with modular and movable elements that can be added or removed as needed. I liked his ideas; for each scene he introduces elements that give it a distinct character without distracting our attention.”

Javier Lillo, Beckmesser

Opera guide

Female leaders in a masculine world – The director’s thoughts

In the opera written 190 years ago by Gaetano Donizetti and Giuseppe Bardari, two charismatic women – two great personalities – clash in a masculine world. The tragic fate of Mary Stuart has inspired numerous works of art. Elizabeth’s forty-four-year reign is often referred to as England’s Golden Age. She yielded neither to courtly pressure nor to suitors, establishing the cult of the Virgin Queen. The two Tudor queens are radically different in character. While the Protestant Elizabeth is chaste, cautious, self-sacrificing, and tactical, the Catholic Mary is a man-eater, hot-headed, passionate, and open. They have two things in common: their love for England and for the Earl of Leicester.

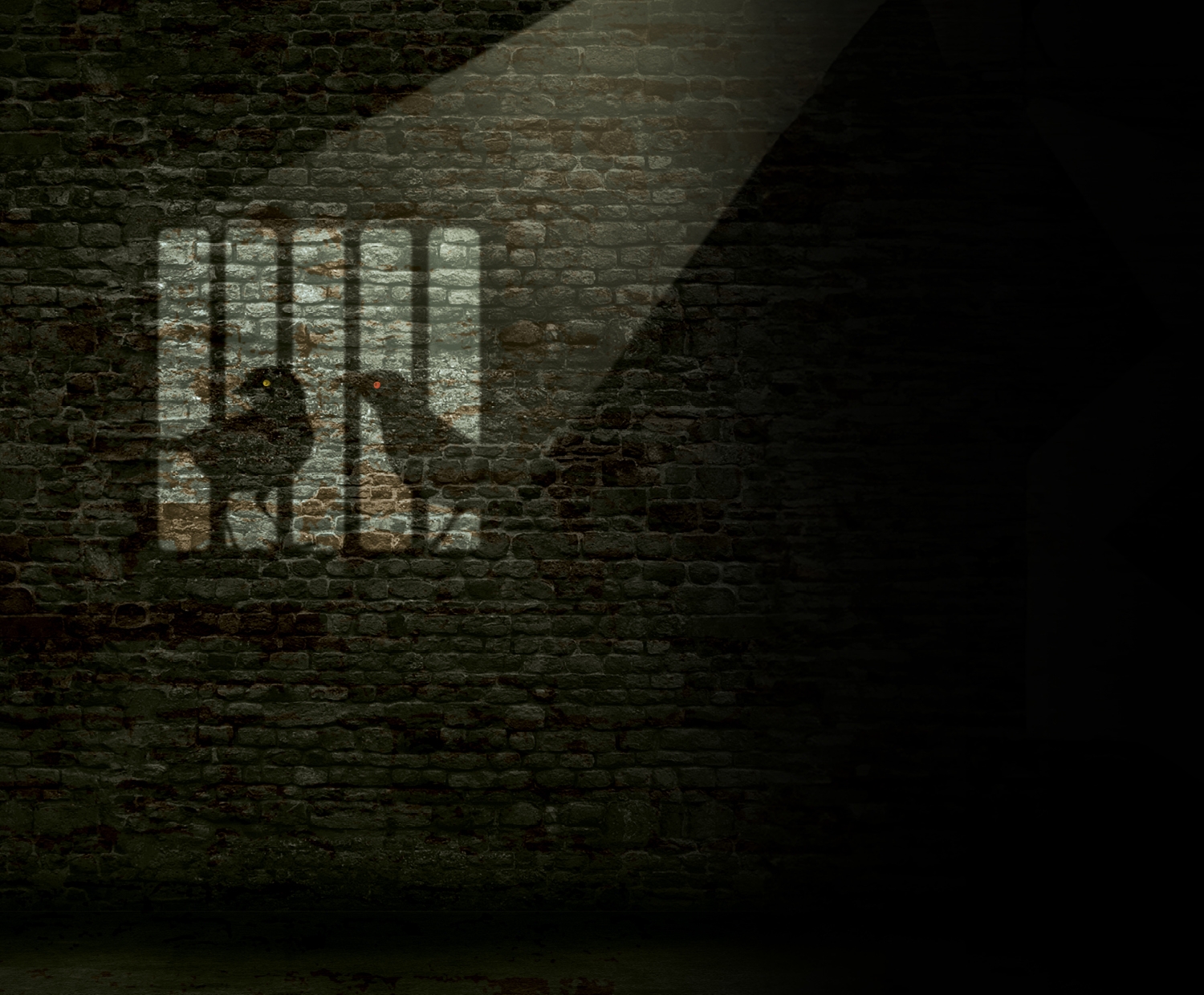

The setting of Act I is the world of imperial constraint. Familiar themes shine through this historical tale, such as the question of external and internal freedom, or the price a female leader must pay in a masculine world. The functioning of the state hinges on the extreme restriction of a woman’s fate: Protestant England must unite with Catholic France, while protests erupt before the royal palace demanding Mary’s release. Elizabeth must account for every breath she takes to Parliament, the military, and the people, caught in the crossfire of political and religious intrigue. At the height of power, human relationships no longer offer connection. She awaits a divine sign to help her decide Mary’s fate. A snow-white halo appears and reappears throughout the performance.

The courtyard of Mary’s prison in Act II offers the illusion of true freedom: prison is reality, yet the distant blue sea evokes the feeling of infinity. The two queens meet under the open sky. Elizabeth visits Mary’s prison under the pretence of a hunt – symbolic in nature, as the prey is Mary herself. A person becomes vulnerable to their enemy when they have not faced their own sins. Above them, the snow-white halo appears; within its glowing circle, they pursue and tear at one another. Mary becomes truly free when she calls Elizabeth a whore and a bastard, shedding the last spark of her need to conform. In this way, Mary becomes free, while Elizabeth becomes a prisoner – trapped by her own position. By the end of the performance, their statuses are reversed. Leicester gives his heart to Mary, depriving Elizabeth of love. Donizetti’s opera is heartbreakingly lyrical and emotional; above all its motifs rises the Catholic apotheosis – not in the religious sense. Mary’s confession and prayer represent a kind of self-knowledge and purification, a form of transcendental freedom: the conscious transcendence of human mind and soul, liberating itself from all fear and earthly constraints.

Máté Szabó

Bel canto in the service of drama – In conversation with conductor Martin Rajna

What do you find most unique about Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda?

The story of Maria Stuarda is a powerful drama about power and morality, identity and betrayal, personal desire and political obligation. Mary and Elizabeth represent not just two rulers but two worldviews. Yet neither of them is depicted as entirely “good” or “evil.” We see two equally intelligent, strong, and yet vulnerable personalities, two rulers who are nevertheless deeply exposed to their emotions and internal compulsions. Although Donizetti’s music is magnificent, for me, the real power of the work lies in this exceptionally strong story. What interests me most are the grave consequences of the blurred lines between political and personal relationships.

Musicology classifies Donizetti as a bel canto composer. Are we dealing with a bel canto opera here?

Absolutely. Donizetti employs the most extreme tools of vocal virtuosity, but never for their own sake. His aim is always to precisely express the dramatic situation. As it is typical in bel canto opera, the focus lies heavily on the vocal lines, and the orchestra takes a back seat as a dramatic tool. Yet the vocal parts are composed with such exceptional invention and poetry that the audience is left fully satisfied.

How is the title character portrayed musically?

Mary’s musical material is particularly intimate, much more so than that of the other characters. We see her primarily not as a monarch, but as a human being, and this greatly shapes the music composed for her role. Her lyrical, sentimental musical character creates a strong contrast with Elizabeth’s, who appears to me as a much more sanguine and impulsive figure in Donizetti’s opera.

What do you make of both queens being sopranos?

Both queens are written as sopranos, but it is worth noting that Elizabeth’s role is composed lower, which also reflects the character traits I mentioned earlier. To me, it actually requires a darker mezzo-soprano timbre. This further heightens the contrast between the two characters, not only through the nature of their musical material but also in their vocal colour.

The Hungarian State Opera performs Donizetti’s works fairly often, yet Maria Stuarda is only now being premiered in Hungary. Why do you think it has not been staged here until now?

Maria Stuarda is not one of Donizetti’s “hits”, it does not contain many widely known or popular arias. Even abroad, it is not performed nearly as frequently as L’elisir d’amore, Don Pasquale, or Lucia di Lammermoor. Even among the Tudor operas, Anna Bolena is perhaps more popular. Also, a rare and fortunate alignment is needed in an opera company’s life: you must have two singers capable of mastering and dazzlingly performing the challenging female lead roles. We are fortunate that this is one such moment at the OPERA, thanks to the talents of Klára Kolonits, Gabriella Balga, and Orsolya Sáfár. It is high time for Maria Stuarda, which has enjoyed great success abroad, to find its place in the Hungarian repertoire.

What do you regard the most important moment in the opera?

My favourite moment is the prayer in the opera’s final scene. Mary, having confronted her sins, approaches her supporters spiritually purified and accepting her fate. Together they kneel and begin to pray. It is one of the most beautiful few minutes in Donizetti’s entire output, a profoundly simple melody, accompanied by an exquisitely delicate orchestration. Perhaps it is this very simplicity that makes it so chilling.

Interview conducted by Diána Eszter Mátrai

William Ashbrook: Maria Stuarda

Maria Stuarda is a tragedia lirica in two or three acts by Gaetano Donizetti to a libretto by Giuseppe Bardari after Andrea Maffei’s translation (1830) of Friedrich von Schiller’s Maria Stuart. It premiered in Milan, Teatro alla Scala, on 30 December 1835.

This work was originally intended by Donizetti as a vehicle for his favourite prima donna, Giuseppina Ronzi De Begnis, but when it was in rehearsal at the Teatro di San Carlo, Naples, the king personally forbade its performance. Donizetti cobbled much of the score into a work with a different plot, Buondelmonte, with new recitatives and other changes, given at Naples on 18 October 1834. But Maria Malibran (Spanish mezzo-soprano) became enthused with the subject of Mary Stuart and insisted on appearing in the opera at La Scala, where she ignored the censor’s changes and caused the opera to be banned by the local authorities. In sanitized form, the work was given occasionally in Italy in the ensuing years. Its first 20th-century revival was at Bergamo in 1958 and it speedily re-entered the repertory. […]

The critical edition based on the recovered autograph reveals an interesting example of Donizetti’s practice of self-borrowing. Two numbers from Maria Stuarda, which Donizetti seems to have given up as a lost cause some time after its suppression in Milan, were later re-used in La favorite: the opening chorus at Westminster and the stretta to the first finale. After Stuarda, this ensemble at one time formed part of an apparently never-completed project, Adelaide, and from there it went into L’ange de Nisida before coming to rest at the end of Act 3 of La favorite. For the rifacimento of Maria Stuarda at San Carlo in 1865 these numbers were replaced, as they were now familiar from their context in La favorite. It is in this inaccurate version that the opera has become widely known in the 20th century. […]

There are a number of interesting features in this score. The extended Act 1 finale (the scene of the confrontation – historically untrue, of course – between the two queens) is unusual in that the middle section, the materia di mezzo, is longer than the Larghetto and the stretta combined; it shows more clearly perhaps than anywhere else in Donizetti’s output his intense interest in dramatic immediacy and potency. The Larghetto of this finale, a canonic sextet, is the source of a remarkably similar passage in Verdi’s Nabucco. One of the most impressive numbers in Maria Stuarda is the eloquent prayer in the final scene; extensively revised, this melody was to form the basis for the ensemble at the end of Act 1 of Linda di Chamounix. Mary’s confession duet with Talbot and her aria-finale are among the most affecting moments in the opera – indeed, in Donizetti’s entire output.