Mefistofele

Details

In Brief

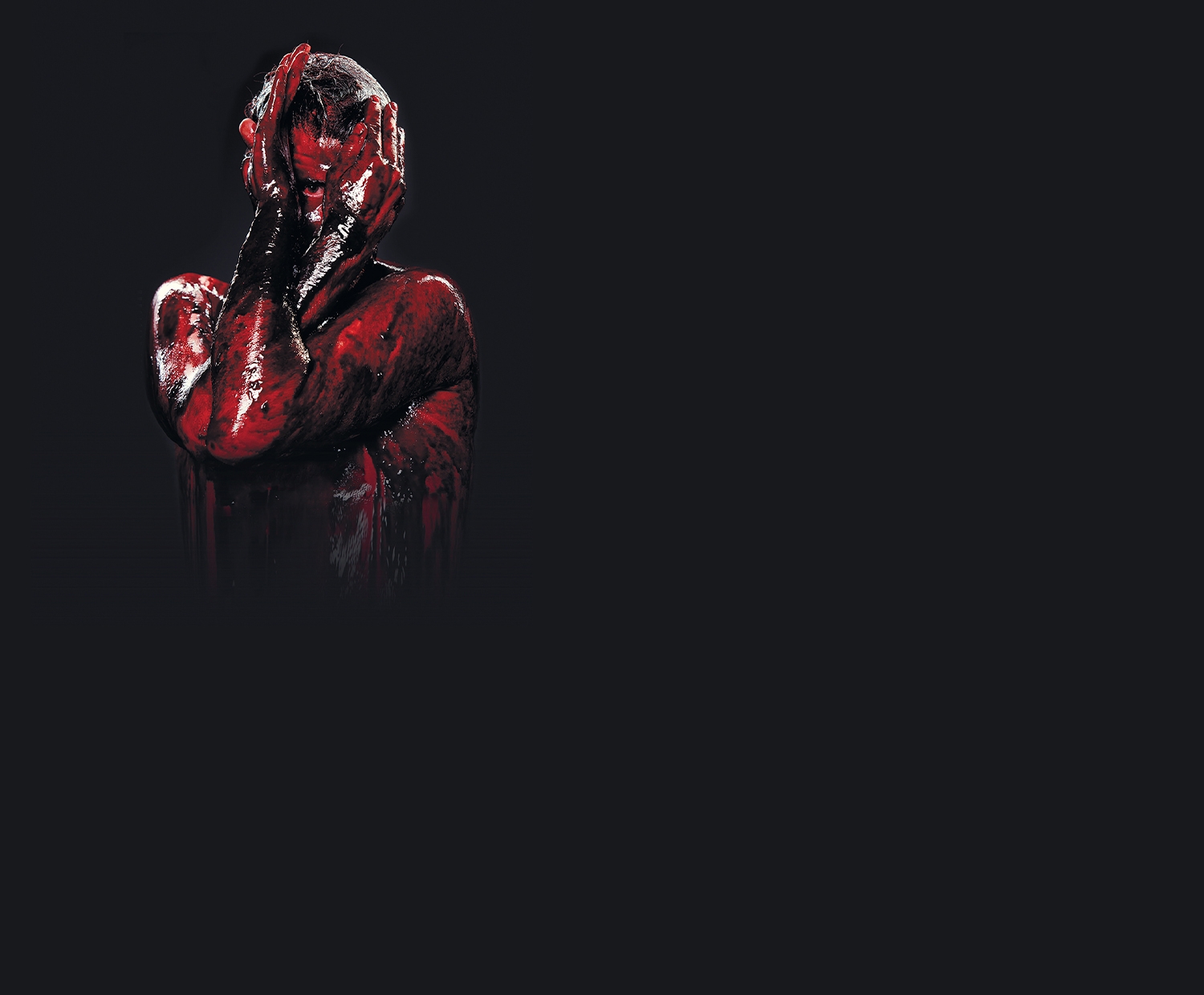

Arrigo Boito is one of the most unique figures in the history of music, not least of all because of his work as a poet: he is responsible for some of the finest librettos ever written for opera (including, for example, Otello). Smitten with Wagner and metaphysics, it's no surprise that he became enamoured with Goethe's Faust, in particularly with the figure of the devil. Mefistofele is his sole completed opera for which he also composed the music. Balázs Kovalik's thrilling production focuses on the mystery of the eternal duel between God against Satan, using powerful imagery to amplify Boito's own personalised poetic treatment of the subject. "The greatest mystery of all isn't the fact that one is thrust into the infinity of creation and the cosmos, but rather that in one in captivity there, we become aware of thoughts powerful enough to make us doubt that our lives are not simply fleeting moments of nothingness after all." (Béla Hamvas)

Parental guidance

Due to its topic, this performance is not recommended for children younger than 16.

Events

Premiere: June 7, 1885

Synopsis

Media

Reviews

„Arrigo Boito meant to give the devil his due in Mefistofele by casting him in the central role. But Balázs Kovalik’s opulent staging at the Hungarian State Opera means that Satan must struggle not only against God, but at least occasionally for the attention of the audience. The reason? The stage magic of Kovalik and his crew occasionally threatens to overwhelm the principals. But in a good way.”

George Jahn, Bachtrack

Opera guide

Introduction

Boito is known primarily as Verdi’s finest librettist, although their relationship was not harmonious at first. The young Boito was one of the bohemian, anarchistic, would-be geniuses of Italian culture; in his sharply critical writings, for example, he demanded an immediate stylistic shift in Italian opera as an advocate of the Germanic operatic direction, which Verdi took as a personal attack. His artistic career was also marked by a constant inner division: he could not decide between literature and music. At the time of the premiere of Mefistofele he was twenty-six years old: the refreshing quality and unheard-of boldness of the undertaking may have been responsible for the fiasco at the premiere, yet overall it nevertheless had a positive effect on the music’s diversity and energy. Boito likewise failed to shape Goethe’s masterpiece into a philosophical, speculative opera (that would only be achieved by Busoni, albeit one enjoyed exclusively by connoisseurs), but he still managed to surpass Gounod’s simplifying approach.

Mefistofele is a better work than Gounod’s Faust, even though the latter remains more popular to this day. The picture assembled from mosaics of fantastic magical journeys focuses primarily on the conflict between God and Satan; love, sex, and pleasure (though there is plenty of them) are secondary. The ambitious prologue is a tour de force in its own right: its monumentality, its variety that blends the exalted with playfulness, construction with destruction, a sense of fate with timelessness, and its depiction of the relationship between heavenly and earthly beings are musically astonishing as well (the cherubs, for instance, are brought to life by the voices of twenty-four boy sopranos). Throughout, the central figure of the piece remains Mefistofele, who flaunts his demonic power and cynicism in two fearsomely resonant and impressive monologues (“Son lo spirito che nega sempre tutto,” “Ecco il mondo”), beautifully counterbalanced by Faust’s dreamy aria “Dai campi, dai prati” or his sweeping romance from Act IV (“Giunto sul passo estremo”). Another similarly popular part of the opera is the duet “Lontano, lontano,” which we owe to a process of adaptation and rearrangement (the composer originally intended it for his opera Ero e Leandro, whose libretto he later handed over to Bottesini).

Not every part of Mefistofele burns at the same intensity, but for the modern director its cosmic time-travel character, its vitality that plays with existential stakes, and its unobtrusive yet inviting philosophy offer a fantastic visual, acoustic, and dramaturgical field. Kovalik Balázs’s benchmark-setting production made these possibilities unmistakably clear. Already the Kovalik-style shaping of the bustling, frightening prologue that sets vast stage crowds in motion signalled that the work, in sure hands, can be transformed into a uniquely modern aesthetic experience. The opera’s opening toward popular culture is perhaps best demonstrated by the fact that a characteristic passage of the Walpurgis Night (“Folletto! Folletto!”) was even incorporated into the music of the film Batman Begins (2005).

Zoltán Csehy

Mocking laughter as a weapon

…he was accused of being too cerebral in his poetry: contrived, artificial, detached from reality. And there is a grain of truth in this. Nature, living life itself, interested him essentially only in its reflection: he delighted in the rays of sunlight through the spinning vanes of his favourite instrument, the radiometer, the light mill; he listened to the roar of the wind on the shores of Lake Garda, in his villa at Sirmione where he was working on Nerone, mediated by an Aeolian harp; and he often took out his kaleidoscope because – so he said – the sight of the endlessly changing combinations of its colourful fragments was, for his creative imagination, an inexhaustible source of musical and poetic inspiration. His temperament, inclined to unbridled extremes, his dualism torn between the opposites of good and evil, God and Satan, the sublime and the grotesque – believing in the all-conquering power of the spirit of evil – was explained by the eminent literary historian Luigi Russo by Boito’s Polish descent on his mother’s side, which “grafted the romantic and fantastical–exotic northern, Slavic culture into his blood.”

Italy, says Benedetto Croce, had no true Romantic literature in the age of Romanticism; only after 1860 did it gain a Romantic poet, in the person of Arrigo Boito. There are those who consider his poetry the outdated voice of a belated, superseded man, whereas in this allegedly belated poet very much alive forces are at work. Boito views reality from a cosmic, universal perspective; he seeks to grasp the essence, and this essence reveals itself to him in the tragic nature of life, in the fatal triumph of death and evil, an absurdity over which he can gain mastery only with the weapon of mocking laughter. It is to this mockery and self-mockery, with which he defends himself against the world and against himself, that he owes the fact that his Romantic pessimism did not drive him to suicide, as it did two of his “dishevelled” poet contemporaries: Emilio Praga and Giovanni Camerana.

György Gábor

The selfish DNA

“Blood is a very special fluid”, says Mephistopheles to Faust. But everything that is found in blood is a product of the instructions written in the language of DNA. The instructions for every single organism on this planet were written in the code language of DNA. This most genius one of all molecules is a combination of stability and flexibility, the greatest possible accuracy and capricious carelessness, tradition and volatile variability. DNA molecules have two unique characteristics: they are able to make copies of themselves, and they control the creation of the mechanism needed to carry out their instructions. In other words, they have the dual ability of reproducing and operating themselves. DNA molecules can reproduce themselves thanks to their own structures, the famous double helix discovered by Watson and Crick. These molecules are made up by two spiral chains. One holds the exact text of the code, as it is to be read, and the other one is the mirror image of the first one. These two chains relate to each other more or less the same way as a photograph and its negative: the negative chain is used to create a new positive chain and vice versa.

Georg Klein