Nixon in China

Details

In Brief

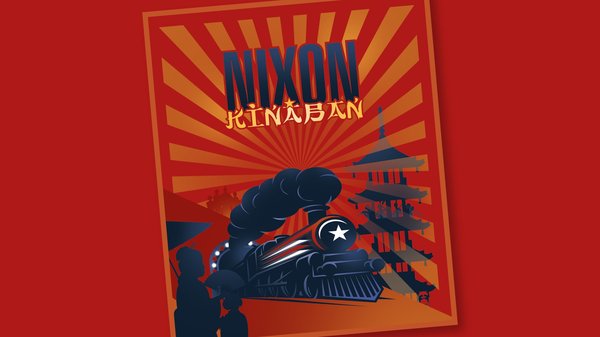

“Nixon in China is John Adams' most successful opera to date and, from the point of view of contemporary American music as a whole, one of the most celebrated operas. In his documentary work, Adams solves the dispassion of news reports with the tools of music, and although the work is about the US president's five-day visit to China, the music is not a conveyor of a political message. The tragicomic power of Adams' music largely stems from the contrast between the two worlds and customs,” writes Zoltán Csehy in his opera guide. Nixon in China has become a globally popular opera performed more frequently in recent times due to the exciting theme of the meeting of the American and Chinese cultures. Its Hungarian premiere was staged by András Almási-Tóth using the special spaces of the Eiffel Art Studios with exciting imagination. “Nixon is like a modern-day Simon Boccanegra whose wife gets an entire act as she learns about the new world of China. The story of the other couple, Mao and his wife, reveals an exciting relationship behind the ideology in a large-scale operatic show,” says the director.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: Sept. 22, 2024

Synopsis

The action takes place in Peking (Beijing), China, February 1972.

Act I

The airfield outside Peking: it is a cold, clear, dry morning: Monday, February 21, 1972. Premier Chou En-lai, accompanied by a small group of officials, strolls onto the runway just as the “Spirit of ’76” taxis into view. President Nixon disembarks. They shake hands and the President sings of his excitement and his fears.

An hour later he is meeting with Chairman Mao. Mao’s conversational armory contains philosophical apothegms, unexpected political observations, and gnomic jokes, and everything he sings is amplified by his secretaries and the Premier. It is not easy for a Westerner to hold his own in such a dialogue.

After the audience with Mao, everyone at the first evening’s banquet is euphoric. The President and Mrs. Nixon manage to exchange a few words before Premier Chou rises to make the first of the evening’s toasts, a tribute to patriotic fraternity. The President replies, toasting the Chinese people and the hope of peace. The toasts continue, with less formality, as the night goes on.

Act II

In the morning, Mrs. Nixon is ushered onstage by her party of guides and journalists. She explains a little of what it feels like for a woman like her to be First Lady, and accepts a glass elephant from the workers at the Peking Glass Factory. She visits the Evergreen People’s Commune and the Summer Palace, where she pauses in the Gate of Longevity and Goodwill to sing, “This is prophetic!” Then, on to the Ming Tombs before sunset.

interval

In the evening, the Nixons attend a performance of The Red Detachment of Women, a revolutionary ballet devised by Mao’s wife, Chiang Ch’ing. The ballet entwines ideological rectitude with Hollywood-style emotion. The Nixons respond to the latter; they are drawn to the downtrodden peasant girl—in fact, they are drawn into the action on the side of simple virtue. This was not precisely what Chiang Ch’ing had in mind. She sings “I am the wife of Mao Tse-tung,” ending with full choral backing.

Act III

The last evening in Peking. The pomp and public displays of the presidential visit are over, and the main players all return to the solitude of their bedrooms. The talk turns to memories of the past. Mao and his wife dance, and the Nixons recall the early days of their marriage during the Second World War, when he was stationed as a naval commander in the Pacific. Chou concludes the opera with the question of whether anything they did was good.

Adapted from a synopsis by Alice Goodman

Media

Reviews

“For the first time, the Hungarian State Opera presented Nixon in China. (…) It was staged in the company’s Eiffel Arts Studio’s Locomotive Hall using an experimental theatre design style. (…) Cannily, the presence of the decommissioned train perfectly suited the sound score of this opera’s repetitive accompaniment energy.”

Alexandra Ivanoff, Papageno

“Most of the action took place on three platforms. These were sometimes used independently of one another, which was especially effective in the ballet scene. At other times, the action shifted from one platform to another, as for example during Pat Nixon’s visit. At yet other moments, we could see characters on the currently unused podiums who were not participating in the given scene, but the clever spatial arrangement made it clear that Zhou Enlai or Kissinger were important players in the background as well. (…) The refined and impressive use of the entire space (together with the enormous, astonishingly good, and seemingly double-sized chorus) allowed the monumental music to come fully into its own.”

Simon A. Bird, Opera Reviews

“The production seen in Budapest is first-rate, excellent in every respect, starting with the hall in which it was presented. But is this an opera? In my view, we can state immediately: yes, it is indeed a real opera. There is continuous singing, no spoken dialogue, yet there are arias, duets, trios, and quartets, not to mention the chorus. And of course, all of this takes place live, with a large orchestra. (…) The creators thought through everything down to the smallest detail, and their concept works with clockwork precision.”

Alexander Zhurbin, Masterskayja

Opera guide

In the mirror of objective and subjective reality – The director’s thoughts

Politics, in time, becomes history, history becomes myth, which is only a step away from the world of dreams. How far we can get from simple facts! Nixon’s visit to China became history even in its own time, it was dubbed as “The week that changed the world”. It comes as no surprise that the creative trio of Sellars, Goodman, and Adams saw an opportunity in it. The dull facts turn to dream in front of our eyes, the boundary between objective and subjective storytelling is dissolved.

The opera tells the tale in a mirrored structure, or rather, in the refraction of a double mirror. It begins with reality, quoting well-documented events verbatim. However, this reality seems to become an inner reality all the time, and the innermost thoughts of the characters are revealed. The second act is dominated by subjectivity, first through Pat’s visit to China, then in the stage performance, where the story takes place completely in the world of dreams and visions. It is all foretold by a few previous moments as well as the presence of the three secretaries in the scene of the “verbatim theatre”. The third act then returns to reality, albeit into a subjective reality behind the political hinterland. The caesura in our performance is in the middle of the second act. Thus, the mirror image is clearly visible: objective reality – inner reality / dream – subjective reality. It is almost a Shakespearean dramaturgy, in a brilliantly modern setting.

As every important work, Nixon in China has also much more to tell than the original story, it also finds its contemporary interpretation. Although the relationship between China and the rest of the world is a current and global matter, the opera attempts to explore more than that, namely, a most crucial problem in Europe and all around the world: how to get along with each other, how can all the different political, racial, religious, and ethical views, the different cultures, different points of view co-exist? How can we accept anything unfamiliar (you do not need to love them, acceptance is enough) as there is always a greater and more important truth that should be our common goal. Declaring the unknown, the incomprehensible as alien has caused so many problems in the history of the world. Nixon’s visit to China is a perfect example: two nations – unknown, incomprehensible, and opposite to each other – shake hands, because you must and you can co-exist even if your view on the world is completely different. The Hungarian premiere at the Eiffel Art Studios is staged in unusual spaces to have the audience see this “opera show” from different points of view. Adams’ grand opera makes use of all the tools of the genre available to provide an unusual opera experience in a unique re-interpretation even though the word “unusual” is also used in a sense different from the usual.

András Almási-Tóth

Musical minimalism united with monumentality – The conductor’s thoughts

Nixon in China is a strange work, it has a special place not only in the opera repertoire of North America but the entire world. It is an unusual “tableau opera”, very American in style and nowadays it has such a powerful effect as at the time of its world premiere due to the actualities of the political half-past and the audience’s natural or often unnatural interest in the life of TV celebrities. In my opinion, the time for this opera has come – and not only in Hungary but all over the world – to be relevant again as we are all unwitting passengers of the current geopolitical roller coaster for more than a decade.

John Adams uses the tools of minimalism to build an effective and monumental drama on stage. It might seem a contradiction but only seemingly so. It is as if the work is both an opera and a parody of the opera genre in one, in the best sense of the word. The music is both an attractive surface and a vortex that grabs the listener, and neither the story nor the characters can be “swallowed or spat out”. I think that both Peter Sellars, who developed the concept, and the composer really hit the nail on the head with it, and – although it is strictly my opinion – they have not been able to surpass it with any of their subsequent operas. From the iconic characters of an iconic story, an iconic, or if rather, a cult opera was born.

The opera is often compared to the style of Philip Glass. By no means it is surprising if many find the music of composers from the “same school” very similar. Steve Reich managed to compose quite a few truly world-renowned works for chamber ensembles (Tehillim or Music for 18 Musicians), Philip Glass owes his popularity more to the film industry (the sound and image montages of Koyaanisqatsi for instance), while perhaps it was John Adams who made the most of it what we call in the field “classical music business”. He could successfully transform the repetitive and minimalist music in such a way that proved it is not so far from the art of, say, Beethoven or Brahms. Meanwhile, of course, all three authors, including Adams, could create a truly 20th-century American sound.

Every powerful innovation has a liberating effect on contemporary authors or composers of the next generation. The realisation of “oh, you can actually do it like this” is important. My own little private story relates to my own one-act opera Barbie Blue, which was performed in 2018 at the Erkel Theatre as a companion piece to Bluebeard’s Castle by Bartók. Some scenes in the work can be compared to the seven doors in Bartók’s opera, and I intended the Chamber of Treasures scene specifically as an allusion to the music of John Adams. It only became clear to me now, when I had to learn the entire Nixon, that I managed to compose an almost identical rhythmic and harmonic “quotation” at the time without the specific knowledge of the source. This also goes to show that Adams really has his own style and voice, and what he does is very easy to identify with. The sounds mixed in Nixon – amplified strings, a big band, keyboards, percussion – are used by many contemporary composers, and not necessarily just as an afterthought. I find it fascinating how a story lasting several hours can be built from short and catchy pop music elements, and at the same time we see and hear live, flesh-and-blood characters as well as figures from a news flash who lack almost any dramatic character development. This opera is like the musical equivalent of Andy Warhol’s infamous artwork Campbell’s Soup Cans.

Gergely Vajda

The story of a visit

Prelude. The path to the visit

George Kennan, a key figure in post-World War II American foreign policy wrote the following in a secret report: “We have about 50% of the world’s wealth but only 6.3% of its population. This disparity is particularly great as between ourselves and the peoples of Asia. [...] Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity.” On the same day, 24 February 1948, the American ambassador to China requested more weapons from his government to support Chiang Kai-shek in his fight against Mao Tse-tung to prevent China from becoming communist. By this time, the civil war between the supporters of Mao and Chiang Kai-shek had been going on for three years. The two sides, who used to fight as one in the war against Japan, were now sworn enemies: Mao with the help of Soviet intelligence and Chiang Kai-shek backed by the American military.

The fight ends with the 1949 victory of the communists and the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China. Chiang Kai-shek flees to the island of Taiwan, and his government there retains the Chinese seat in the United Nations. Chiang expects his stay in Taiwan to be temporary and hopes for his return to the mainland with American support to overthrow the communists. Only the socialist countries of that time, including the People’s Republic of Hungary officially recognise the People’s Republic of China in 1949. The Cold War is already in full swing, and the populous newcomer to the Soviet bloc – although only 542 million strong at the time – is a serious reinforcement against the United States and its allies.

Ideological differences, however, soon cause a rift between Moscow and Beijing. In 1956, Khrushchev begins to end Stalin’s legacy without having consulted with Mao Tse-tung, who feels betrayed and claims leadership in the international communist movement. To prove that a developed communist state can be created in a short time, Mao launches the Great Leap Forward, which results in an economic catastrophe. The collapse of the economy coupled with drought causes millions of people to starve to death. Mao is criticised severely in his own party. To get rid of his internal opposition, he launches the Cultural Revolution in 1966. The Soviet press openly supports the forces against Mao, and by 1969 the two countries are on the brink of war.

Following the logic of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”, the USA warns the Soviet Union against attacking China. At this point, Mao begins to contemplate the possibility of establishing relations with the Americans – against the Soviet Union. Over ten years into the war in Vietnam against the spread of communism – basically, against the Soviet Union – the USA is in a stalemate. The American public, fatigued and divided by the war, demands peace in Asia. Prior to the 1968 elections, Nixon promises a new policy: “Taking the long view, we simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbours. There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation.”

There was no communication channel between China and the USA at this time, and they were indirectly impeding each other’s efforts. The USA kept supporting the government in Taiwan against Mao, whereas Mao supported the Vietnamese forces fighting against the USA. In the grand chess game of the Cold War, the USA hoped to gain the upper hand over the Soviet Union by appeasement with China. China also thought the friendship with America to be the greatest security against an attack by the Soviet Union.

On 4 April 1971, a surprising event took place. Following a training session for the table tennis world championship in Japan, an American player missed his bus to the hotel, and had to ask for a lift by the Chinese team. He got into conversation with a Chinese player, who presented him with a Chinese silk scarf. Journalists took photos of them getting off the bus, and the photos landed on the table of Mao Tse-tung. Two days later, an official invitation was sent to the American table tennis team, who then arrived in China on 10 April. They played friendly matches, and it was Chou En-lai himself who welcomed them. This is how “ping-pong diplomacy” opened the door to reconciliation between the USA and China. In a rapid succession of events, Henry Kissinger, National Security Advisor to President Richard Nixon made a secret visit to Beijing in the summer of 1971. It was the first time that an American politician discussed international affairs with his counterparts in the People’s Republic of China. The greatest source of contention between them was Taiwan: China was still represented by the Taiwanese government internationally, under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek.

In October 1971, the motion to recognise the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations was passed. It also meant for Taiwan to be removed from the UN, because the People’s Republic did not consent to the idea of “two Chinas”. The USA would have preferred for Taiwan to be officially represented as well, but in the end the “one-China” principle prevailed. In November 1971, the delegates of the Beijing government as the official representatives of China took their seat in the UN Security Council for the first time. Richard Nixon’s visit to China took place in February 1972. The presidential election was to be held in November the same year. Before his departure, Nixon made the following statement to the press: “What we must do is find a way to see that we can have differences without being enemies in war.” Opinion polls showed support for the visit by 68% of the American people.

Attending a ballet

During their visit, President Nixon and his wife attended a ballet. During the Cultural Revolution, the wife of Chairman Mao, Chiang Ch’ing, a former actress, banned all traditional theatre and dance performances. Only eight ideologically pure revolutionary works were to be performed: five Beijing operas, two ballets, and a symphony. The Beijing operas retained traditional vocal technique and acrobatics but introduced contemporary costumes. Ballet as a genre in China was a result of the friendship with the Soviet Union. It was only in 1954 that the first Chinese dance school to teach classical ballet was opened, with the help of Soviet ballet masters. The ballet entitled The Red Detachment of Women, seen by the Nixons, is about a Chinese peasant girl: having been tortured by a landowner, the girl flees to the Red Army, where she becomes a member of the Women’s Detachment. They take their revenge on the landowner, free the people oppressed by him, and the girl becomes Commissar of the Women’s Detachment. The ballet has been performed in China over 4 000 times, and it is still staged from time to time.

Aftermath

At the end of the visit, Nixon and Chou En-lai published a communiqué to announce the end of open hostility and the beginning of normalisation of relations. The most controversial issue was Taiwan, but according to the communiqué, America recognised Taiwan as part of China, and committed itself to removing its troops from the island. This communiqué was to become the political basis of USA– China relations. Nixon described his visit as “the week that changed the world”. In international politics, the phrase “Nixon goes to China” is still a metaphor for a political leader taking an unexpected step. And this week was only the starting point of a series of important events.

After his trip to China, in May 1972, Nixon visited Moscow to sign the SALT I agreement with Leonid Brezhnev. It was the first détente between the two Cold War blocs in the nuclear arms race. In September 1972, Japan recognised the People’s Republic of China. The Japanese prime minister visited Beijing to apologise for the invasion of China and to develop friendly relations. In November 1972, Nixon achieved a landslide victory in the presidential elections. Within two years, however, he was ruined by the Watergate scandal, and forced to resign. In 1976, Mao died. After a two-year interregnum, in 1978, Teng Hsiao-ping became the leader of China, and announced his “reform and opening up”. On 1 January 1979, the United States of America establishes official diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. The same week, a cartoonist of a Chicago newspaper summarises the expectations of the USA: the drawing shows Teng Hsiao-ping as a giant with small traders beneath. His sleeves display the words “China Trade”, while the caption says: “The man with over 800 million customers up his sleeves”. A new world is born.

Ágota Révész