Rigoletto

Opera IC Audiophile series

Details

In Brief

There are evenings when our Opera House cannot perform because rehearsals are ongoing on stage until the evening. There are audience members who can only afford to hear their favourite pieces with a discount. And there are works that, although very popular, cannot be staged every season due to the congestion of productions. All these issues can be solved at once by the Hungarian State Opera’s new IC series, whose name carries the of iron curtain, but which may also gain popularity with the speed of an express train. Even though it will feature in the programme as a regular series beginning only with the next season, we are already presenting this new, semi-staged operatic format that offers more than concert performances on selected evenings during the current one as a preview. The titles are major works by great composers, requiring smaller choruses but offering fewer but particularly significant soloist roles.

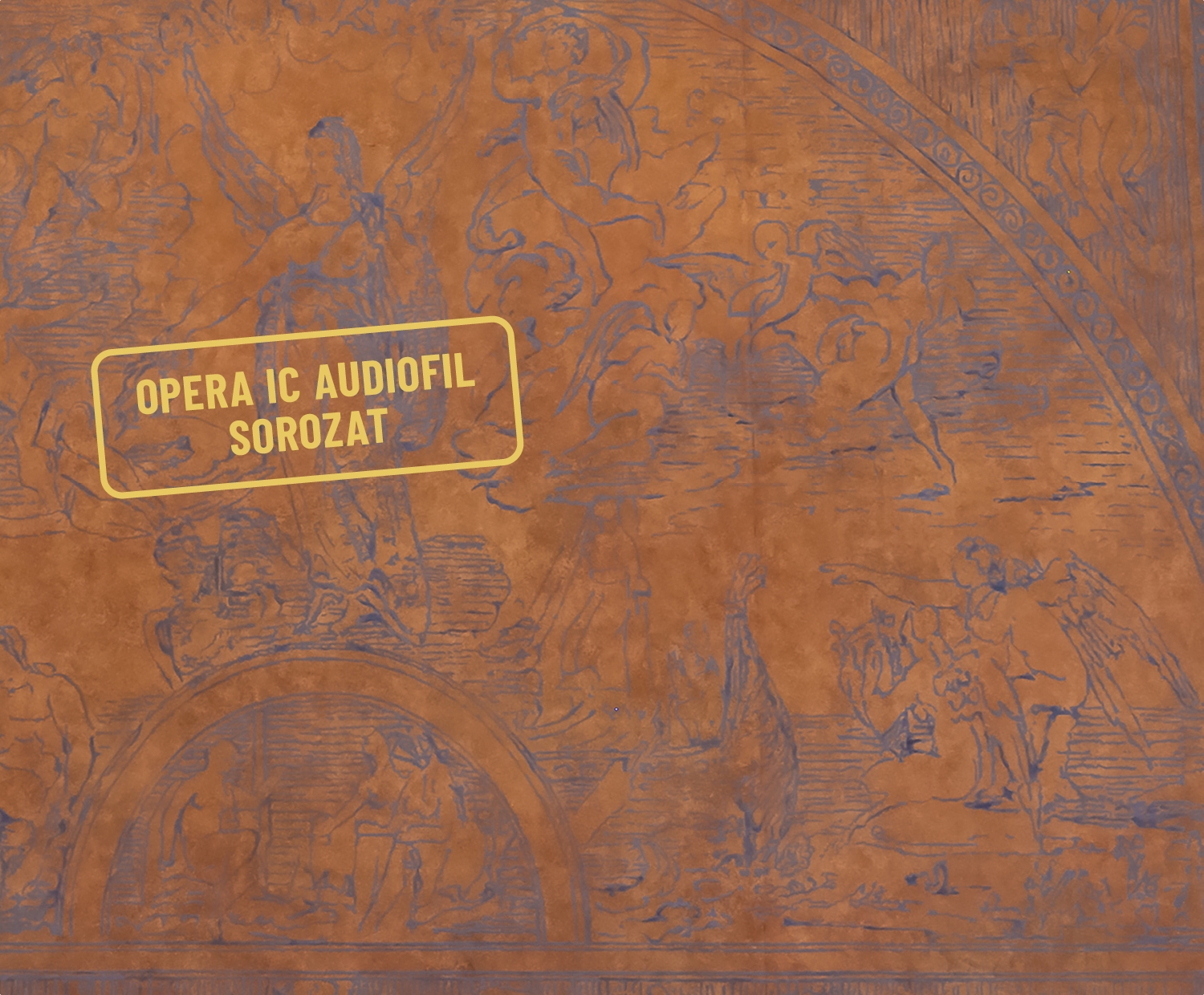

A mere hour after a stage rehearsal, visitors having purchased their ticket with a 20% discount find the iron curtain of the Opera House lowered. The massive double steel plate, covering a surface of 170 m², does not only conceal the set of the next production behind it but also serve as an acoustic reflector meeting audiophile standards. Onto this enormous surface, decorated with architect Miklós Ybl’s engravings, we project a unique video installation, with Hungarian and English surtitles displayed at the top. The orchestra takes its usual place in the pit, while the hand-picked, first-rate singers step through the door in the iron curtain to take a seat at the front of the stage, then step into the limelight when it is their turn to sing.

The form is quasi-concert-like, but the soloists do not use sheet music, they appear in period costumes, and can use their faces, hands, and bodies for dramatic gestures. The participating chorus performs from various points of the building to astonish the audience with a powerful 3D sound. From all this, a single, significant, shared experience can emerge: the wonder of sound that feels much closer to the audience, magnifying gestures and offering a far more intense, truly record-quality experience in an auditorium that is thus transformed into one with the best acoustics in Hungary, the concert hall of the Opera House.

In the 2026/27 season, audiophile concert performances of Bluebeard's Castle, Don Giovanni, Rigoletto, and Tosca continue the series started in 2025.

Parental guidance

Events

Synopsis

Scene 1 – A hall in the ducal palace

Scene two – Rigoletto's house and garden and the adjacent street

Opera guide

Introduction

In 1860, the musical journal Zenészeti Lapok wrote only this much about one of the Pest performances of Rigoletto: “On 3 November, Rigoletto was performed – no other misfortune occurred.” The reason for the “misfortune” is not to be sought merely in the singers’ possible performances, but in the tradition of interpretation burdened with moral scruples that initially accompanied the piece (and also Victor Hugo’s drama Le roi s’amuse). “Oh, Le roi s’amuse, the greatest subject of modern times, perhaps even the greatest drama. Triboulet is a creation worthy of Shakespeare! Unlike Ernani! This subject must not be missed,” Verdi wrote to Piave in 1850. According to the censors, however, the subject of the play was “repulsively immoral, obscene, and vulgar,” and it therefore oppressed the composer and librettist from the outset. For Verdi’s protagonist, Rigoletto, completely broke with the operatic pattern up to that point: his character is built from the unusual pairing of a repulsive appearance, sensitive fatherly love, and an awakening passion for social criticism. What is more, at first we encounter in the title figure an immensely unsympathetic and arrogant man, who then undergoes a gradual transformation. Evil must be ugly, good must be beautiful, the noble must always be virtuous, and the ignoble forever base. It was this paradigm that Verdi sentenced to death when he disrupted the harmony of outer and inner qualities and refused to polarize the characters.

Today it is hard to imagine Rigoletto as a misfortune: as long as opera is performed, it can scarcely fall out of the repertoire. The masterpiece, composed in just forty days, besides introducing radically new hero-types (the unidealized, sex-obsessed Duke is at least as provocative as the hunchbacked jester), also realizes a new dramaturgical concept through peculiar atmospheric juxtapositions, motivic connections, and the elaboration of the broad psychological background of chatty, conversational scenes. A few examples of this: the Duke’s boisterous hedonism (think of the evergreen glove aria “Questa o quella” or the opera’s most famous aria in Act III, “La donna è mobile”) stands in stark musical contrast with the glowing sincerity of the love-duet “E il sol dell’anima.” According to an anecdote, Verdi handed over the score of “La donna è mobile” to the tenor singing the Duke only at the last moment, binding not only him but the entire rehearsal staff to complete secrecy: he knew perfectly well that the catchy melody would establish the opera’s reputation, so it could not leak earlier. The thunderous applause after the first stanza almost predestined the encore after the second. But we also encounter more masterful artistic devices: the quartet in Act III (“Bella figlia dell’amore” – the Duke, Maddalena, Rigoletto, and Gilda) is of downright operatic-historical significance. The unravelling of inner conflicts and intentions based on counterpoint, which nonetheless forms a harmonious unity, is clearly a phenomenon that is the specific hallmark of opera’s simultaneous character.

Zoltán Csehy